By David Martinez / Boxing Historian / dmboxing.com

Many people have asked me about former heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan. They say that there’s no footage of him and wonder how we can rate his greatness. Of course the footage isn’t there, and this is why we have historians, books, records and, most importantly, have had people who lived in his era with their assessments.

Many people have asked me about former heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan. They say that there’s no footage of him and wonder how we can rate his greatness. Of course the footage isn’t there, and this is why we have historians, books, records and, most importantly, have had people who lived in his era with their assessments.

I have not personally spoken to anyone from his era which is the late nineteenth century, but the oldest person I have ever had contact with who actually comes close would be boxing historian Al Nelson . He goes back to Bob Fitzsimmons, who beat James J. Corbett to win the heavyweight title, and Corbett was the one who beat Sullivan for that title.

When I was in high school back in the sixties, I wrote a book report on Sullivan and wish I could find that article piece. Who knows where it is today after all these years?

In that article I will never forget my opening sentence: “John L. Sullivan is the first American boxing icon, and he was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts, on October 15, 1858.”

Sullivan’s fame in the boxing ring is remembered by many in boxing circles, even today a hundred and thirty years later .

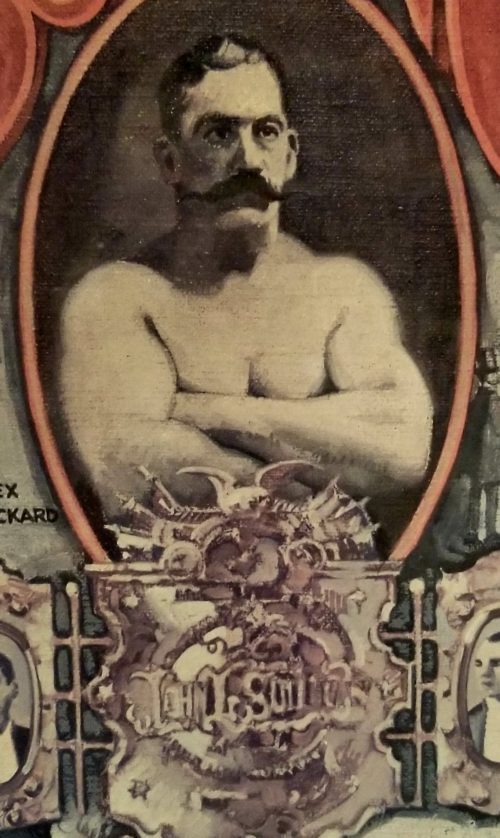

Known as the “Boston Strong Boy”, Sullivan was as strong as they come, at 5’10” and weighing 190 pounds. In high school he excelled in baseball, boxing, and wrestling.

Because his mother wanted him to be a priest, he briefly attended Boston College. But from an early age, Sullivan showed a great proficiency with his fists.

As a teenager he engaged in bar room fights, issuing a challenge that he could lick anyone in the house . He would also compete in weight lifting and in contests throwing beer kegs across the room.

At the age of eighteen, he took to boxing and fought several four round amateur bouts with success.

Then, in 1877, at the Dudley Street Opera House in Boston, Sullivan attended a sparring session/exhibition that featured a seasoned heavyweight boxer, Tom Scannel, who would challenge men from the audience to last three rounds with him before he would knock them out.

On that night, Sullivan urged by the patrons, entered the ring as a contestant. Scannel offered to shake hands with Sullivan before the bell rang, but suddenly and by surprise punched Sullivan and dropped him to the mat . Upon getting up, Sullivan immediately threw a series of rapid punches and with a hard right to the jaw knocked Scannel out of the ring and into the orchestra pit. One could say that this prompted him to enter the world of boxing.

The following year in 1878, Sullivan did just that, beginning his historic professional boxing career with an impressive 5th round knockout victory over Cockey Woods.

In 1880, he boxed exhibitions with well known fighters Mike Donavon, and former champion Joe Goss.

On January 3, 1881, Sullivan would knockout Canadian heavyweight champion Jack Stewart in two rounds, and once again had exhibition matches with Donavon and Goss .

An interesting bout on May 16, 1881 saw Sullivan fight on a barge in the Hudson River to evade the authorities, and he scored an eight-round knockout over John Flood, knocking him down eight times.

With the stage set for a huge fight on February 7, 1882, Sullivan met heavyweight champion Paddy Ryan in Mississippi City, Mississippi for the bare knuckle title. The bout was one-sided as Sullivan dominated Ryan throughout, with the knockout win coming from a straight right to the jaw in round nine.

Sullivan would put together a string of victories, before a bout with British Empire champion Charlie Mitchell on May 14, 1883 at the old Madison Square Garden in New York. Although Sullivan was knocked down in the first round, he would knock Mitchell through the ring ropes in round 2. He continued the onslaught until the end came in round 3 when Metropolitan police Captain Williams stopped the bout by official order from referee Billy Mahoney. Five years later, on March 10, 1888, the two met at the estate of Baron Rothschild in Chantilly, France. In a steady down-pour of rain, the thirty-nine round bout lasted 3 hours, 10 minutes, 55 seconds, before ending in a draw. The fight was governed by the London (bare knuckles) Prize Rules.

On July 8, 1889, Sullivan fought a most historic bout with Jake Kilrain which was the last significant bare knuckle fight in boxing. For the first time in Sullivan’s career, he had ballooned up to about 40 pounds over his fighting weight, so he entered a serious weight training with champion wrestler William Muldoon to trim down. After a slow start to the fight, Sullivan got the better of Kilrain and won by knockout, when Kilrain’s corner threw in the towel after the end of the 75th round. The bout lasted two hours and fifteen minutes.

On July 8, 1889, Sullivan fought a most historic bout with Jake Kilrain which was the last significant bare knuckle fight in boxing. For the first time in Sullivan’s career, he had ballooned up to about 40 pounds over his fighting weight, so he entered a serious weight training with champion wrestler William Muldoon to trim down. After a slow start to the fight, Sullivan got the better of Kilrain and won by knockout, when Kilrain’s corner threw in the towel after the end of the 75th round. The bout lasted two hours and fifteen minutes.

After defeating Kilrain, he did not fight for over three years, instead touring as a cast member in a play called “Honest Hearts and Willing Hands”. He did, however, continue to box in friendly exhibitions. In 1891, he sparred against Jim Corbett on June 26, and Joe Choynski on December 20 with both exhibitions in San Francisco, California.

March 15, 1892 was the date that Sullivan agreed to defend his world heavyweight title against Corbett, with the bout officially announced to take place on September 7, 1892.

Sullivan opened up as a 4 to 1 betting favorite in the bout set to take place at the Olympic Club in New Orleans, under the Marquess of Queensberry Rules. Both fighters were to wear five-ounce gloves.

The two had contrasting styles, with the older, powerful, steadfast Sullivan facing the peerless boxer-puncher ability of the younger Corbett.

In the fight, Corbett fought from the outside keeping Sullivan at bay for the first twelve rounds, using effective jabs and managing his distance well. By round seventeen Sullivan was showing signs of weariness, and it became apparent that Corbett was in complete control at this juncture of the fight.

Corbett stopped Sullivan for his first defeat in the 21st round, and a new heavyweight champion was crowned – James J. Corbett.

After a couple of exhibitions against Corbett and Tom Sharkey and a knockout win in Grand Rapids, Michigan over Jack McCormick on March 1, 1905, the man dubbed the “Boston Strong Boy”, Irish-American boxer John Lawrence Sullivan retired from boxing. He continued with various positions such as stage actor, celebrity speaker, sports reporter, and bar owner. He also gave up his lifelong addiction to alcohol and became a prohibition lecturer.

His professional ring record was outstanding with 47 wins, 1 loss, 2 draws, 1 no-contest, and 38 knockouts.

Boxing Historian Bert Sugar ranks Sullivan #54 on his list of the greatest boxers of all time. I personally rank him #17 among the greatest heavyweights of all time.

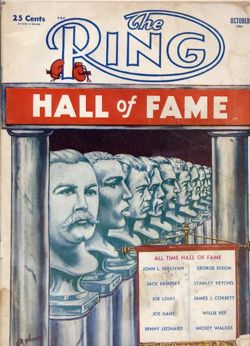

Sullivan was an inaugural member of The Ring Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954, was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1983, and inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

Sullivan left an indelible imprint on boxing in America and was a hero to many. He was never noted for a prejudice against blacks, but in his days in the ring, he drew the color line on his own behalf. The logical opponent was Peter Jackson, but Sullivan would not hear of it quoting “I will not fight a Negro, I never have and I never will. Yours truly… “. And that was that, as far as Jackson’s quest for a heavyweight title.

John L. Sullivan died from a heart attack on February 2, 1918 while residing at his home in Abington, Massachusetts, at the age of 59.